|

By Gabriella Goldstein In March of 2020, the Tufts European Center was preparing for what promised to be a busy summer season at the Prieuré in Talloires. Our signature programs— Tufts in Talloires, Tufts in Annecy, and Tufts Summit— were well subscribed; our meeting and events calendar was full; and we were just a few weeks away from departing for Talloires. As we all know, the COVID-19 pandemic derailed all those plans. It sent Tufts students home from the main Medford campus to finish the spring semester remotely. It closed international borders and pushed France into lockdown. We on the Prieuré staff had no choice but to cancel all of our 2020 summer programs. Worse still, the timing and abruptness of the shutdown left us insufficient time to implement an alternative delivery method for our programs. To ensure that our season could still be productive, we re-directed our energies to other important projects for the Center: We created a new and updated website; we launched an electronic newsletter; we spent many hours attending webinars to improve our skills; and we began planning for summer 2021. Although the new year brought hope for mass vaccinations and herd immunity, it also brought COVID variants, new global pandemic surges, and continuing limitations on international travel— all of which made it very clear that a return to Talloires wouldn’t be possible for summer 2021. Will students buy it? With heavy hearts, in January we made the decision to adopt a virtual format for our 2021 Tufts in Talloires and Tufts Summit programs (for college and high school students, respectively). “I was disappointed, but also not surprised, given how the world is still attempting to manage the pandemic,” said Sarah Craver, assistant director of the European Center. “I recognize the paramount importance of keeping our communities safe, and of allowing our faculty (and ourselves) time to create a rich, exciting virtual experience for our students,” Obviously, a virtual community cannot replace face-to-face interactions, not to mention real life immersion in the HauteSavoie culture. Nevertheless, we are very excited about the new ways that we will provide engaging international content for students. All of our classes will include virtual guest speakers from Talloires/Annecy/Geneva and beyond, who will interact with students and help provide the international perspective we have always sought to include in our programs. If we can’t bring students to Talloires, we will bring Talloires to them! Will students buy this sales pitch? “Virtual learning definitely opens up some unique opportunities,” comments one of our former Talloires students, Taite Pierson. “It’s easier to see everyone in the class, and the chat function is really great for asking questions and making comments. I’ve been able to connect with people from all over the world in online learning environments, people I probably wouldn’t have otherwise met.” Tufts senior Lily Russell offered, “It can be challenging to take classes online, but it can also allow for so much more flexibility in my day, which I enjoy. There is no commute to class, and I have the freedom to be located where I wish to be. Ultimately, I do wish all of my courses were in person this semester. But online classes are still rewarding and engaging.” And how will we maintain the MacJannet legacy in all of this? “The MacJannet legacy is not only about a place—Talloires—it is about respect, diversity, understanding, and learning,” suggested our staff assistant, Kim DeCrescenzo. “The values go beyond a physical building and can be understood and appreciated from anywhere in the world.” Sarah Craver added, “Our approach reflects values that were crucial to the MacJannets: tenacity, persistence, and keeping learning at the heart of any experience. When I think of the times that the MacJannets lived through, I think of the challenges that they faced and the creativity with which they had to respond. We must not only reflect these values, but we must also strengthen our community by getting to know our students well and developing an environment of support and rich learning that they will remember for a long time!” For the Tufts European Center, the summer of 2021 will present both challenges and opportunities. With a strong legacy to guide us, a healthy dose of energy and imagination, an incredibly dedicated staff and faculty, and a supportive community both in the U.S. and in Talloires, we are confident that it will be a very successful experience for all of us. As you see, we are heirs to the MacJannet tradition. What else could we be but optimists? Gabriella Goldstein is director of the Tufts European Center in Talloires, France.

0 Comments

1. The right person will come along By Sally Pym Shortly after I became assistant director of the Tufts European Center in Talloires, Charlotte MacJannet asked me to organize a concert for a young pianist and singer in MacJannet Hall at the Prieuré. In those days— the early 1990s— the director came to Talloires for only two weeks every summer, so the responsibility for Charlotte’s request fell entirely on my shoulders as the Prieuré’s de facto on-site manager. The date Charlotte specified was a Sunday— normally my only day off. The program would require me not only to set up the hall that morning but also to publicize the event beforehand in Talloires and the nearby villages. But declining this task was not an option. Charlotte at this point was well into her 90s, the living soul of the Prieuré; she had been unfailingly gracious to me since my arrival; and in any case, Mrs. Mac was not someone you could reasonably refuse any request. The morning of the concert, as the staff and I set up the chairs and the piano in MacJannet Hall under Charlotte’s watchful eye, the pianist phoned to inform me that an emergency had come up and he would have to cancel his appearance. It was 11 a.m.; the concert was scheduled for 2 p.m. I was beside myself. In just three hours, the audience would arrive— an audience I had personally drummed up. As I saw it, my credibility as the Prieuré’s new assistant director was on the line. To my surprise, Charlotte seemed not the least bit perturbed. “It’s all right, my dear,” she said serenely. “Come with me.” She led me outside, walked me halfway down the front steps of the Prieuré— she was pretty agile even in her 90s— and bade me sit down beside her on the steps. Here she reassuringly put her hand on my knee. “Sally,” she explained, “if we wait here, the right person will come along.” She was aware of my stress but seemed oblivious to the gravity of our quandary. We sat there quietly together until, to my astonishment, about 15 minutes later, a stranger walked down the Prieuré driveway. Together, Mrs. Mac and I descended the steps to greet him. In the process of making our introductions, we asked him almost flippantly if by any chance he was a pianist. When he answered affirmatively, Charlotte invited him to come upstairs and perform at our concert that afternoon. And so he did. That was a wonderful lesson for me as an administrator: If things don’t turn out exactly as you planned, have faith that the unknown alternative might turn out to be just as good or even better. Ever since that day, whenever a colleague panics over some unexpected change in plans, I find myself echoing Charlotte: “The right person will come along.” I subsequently became the Prieuré’s full-time director in 1995. Charlotte died in 1999 at the age of 98. Not long after that, my assistant director informed me that she would be leaving. At first I was devastated. Then I channeled Charlotte and reminded myself: “The right person will come along.” And so she did. The replacement I hired was Gabriella Goldstein, who succeeded me in 2002 and has run the Prieuré for Tufts skillfully and humanely ever since. Sally Pym was assistant director of the Tufts University European Center from 1991 to 1995 and served as director until 2002. She now lives in Venice, Florida. 2. Trust Mother Nature By Dan Rottenberg In the summer of 1974, my wife and I flew from Philadelphia to Talloires for a reunion in honor of Donald MacJannet’s 80th birthday. It was Barbara’s first visit to France, and my first since my final summer as a MacJannet camper 19 years earlier. In the interim, Donald and Charlotte had purchased the thousand-year old Prieuré in Talloires and transformed it from an ancient ruin into a uniquely gracious conference center. Charlotte was naturally eager to show off this marvelously restored property to her visitors— especially those who, like us, were marinated in an urban American sensibility. As she led us through the Prieuré’s nooks and crannies, Barbara was astonished to notice that the building’s many windows all lacked screens. “But how do you keep out the flies?” Barbara asked. “My dear,” Charlotte replied, “when nature is in the balance, Mother Nature takes care of the flies.” It was a concept that simply had never occurred to us. (Nearly half a century later, the Prieuré continues to function blissfully without screens on its windows. In fact, says director Gabriella Goldstein, “I don’t believe I have ever seen screens on any windows in Talloires. I think it is very much an American thing.”) Journalist Dan Rottenberg is editor of Les Entretiens and a MacJannet Foundation trustee. He lives in Philadelphia. 3. Leave time for tea By Mary Van Bibber Harris In 1970-71, when I was a master’s degree candidate at the Fletcher School at Tufts University, I spent the school year studying at the Graduate Institute of International Affairs in Geneva. In that capacity, I was a direct beneficiary of the exchange program inspired and partially funded by Donald and Charlotte MacJannet. Out of gratitude for this opportunity, I offered to help Mr. Mac with some of his voluminous correspondence. Each week I made my way to their apartment building in Geneva’s Old Town, climbed the three wide, worn flights, and rang the buzzer. Either Mr. or Mrs. Mac would greet me, and for the next several hours they engaged in a friendly tug of egos to see which of them would capture more of my time. Mr. Mac often did have correspondence that needed typing, since the MacJannet Foundation was in its infancy and he was eager to plant its seeds. But Mrs. Mac had other priorities, or so it seemed. She felt strongly that more might be gained by the three of us talking together. Consequently, quite soon, her head would pop around the corner of Mr. Mac’s narrow study and exclaim, “It’s time for tea.” At this point I would put aside Mr. Mac’s letters for my next visit, and the three of us would engage in conversations ranging far and wide. In this manner, I came to know this extraordinary couple in both a professional capacity (through Mr. Mac’s letters) and a personal capacity (through Mrs. Mac’s tea). Only in retrospect do I appreciate Mrs. Mac’s indirect method: Over tea, we might not accomplish any work; but on the other hand, we might discover some much more important purpose that hadn’t previously occurred to us. When I left Geneva to return to Fletcher as an administrator, part of my job involved nurturing the Macs’ Fletcher-Geneva exchange program, so my yearly visits to Geneva also included time at their apartment. On one of those visits, we were having tea when Jean Mayer, then president of Tufts, arrived. He had come to learn more about the Prieuré in Talloires, which the Macs had acquired in 1968 as a ruin, then restored, and then offered to Tufts as a gift. Mrs. Mac, naturally, invited Mayer to join us for tea. Next thing I knew, I was in a car with the three of them, driving to Talloires— a 45-minute trip consumed entirely by the MacJannets’ enthusiastic descriptions of the restoration work they had already accomplished at the Prieuré. There is little doubt in my mind that President Mayer decided then and there to accept the Macs’ offer to donate the building to Tufts— which he did in 1978. Not many years later, President Mayer asked me to take over the directorship of that property, which had become the Tufts European Center. The lesson learned? Always take time for tea. Mary Harris was director of the Tufts University European Center from 1982 to 1989 as well as a longtime trustee of the MacJannet Foundation. She lives in Santa Barbara, California. 4. Life is like a book By Caren Black Deardorf I worked at Le Prieuré from 1986 to 1992 as staff and assistant director, living in Talloires every year from March through October. And in 1991, in preparation for the 1992 Winter Olympics at Albertville, I stayed on through the winter because the Prieuré had been designated as headquarters for the U.S. Olympic team. During those winter months, I also volunteered with the Quakers at the United Nations in Geneva. Charlotte MacJannet, who was 90 at the time, had kindly offered to have me stay one night a week at her lovely apartment in Geneva’s Old Town. One afternoon over tea, I was ruminating about my future, with all the anxiety of a 25-year-old who has no idea what to do with her life. Mrs. Mac, always the good listener, nodded and smiled without interrupting. When I finally paused, she firmly took my hand. “You know, Caren,” she said, “you worry too much about your future. You are where you are supposed to be right now, and each new door will open at the right time. Look at my life. “In my 20’s, I was living in the Nordics, where I started a dance school for Eurythmics. “In my 30s, I met and married Mr. Mac and we grew and ran the American school near Paris and the MacJannet camp on Lake Annecy. “In my 40s, due to the war, we lived in Sun Valley [Idaho] and adapted our school and camp there while still raising funds for orphans in France. “In my 50s, we were back in France and purchased the Priory in Talloires. We put all our passion and the energy of many volunteers into renovating the building so that we could host artists, musicians, dignitaries and all who were interested in cross-cultural exchange.” And so she continued through each decade of her life, in each of which she had lived out an entire book’s worth of adventure and impact on the world. “So, my dear, “she concluded, “just take the next step, focus on how you are going to change the world, and the rest will come.” I have followed this advice often in my life and also passed it on to many of the people I’ve been blessed to mentor. If we are lucky, our lives will unfold like Charlotte’s— as a series of chapters in a book, each offering unexpected opportunities to expand our lives while changing the world. Caren Black Deardorf, a MacJannet Foundation trustee, is chief commercial officer at Ohana Biosciences Inc., based in Cambridge, Mass. She lives in nearby Lexington. 5. What really matters

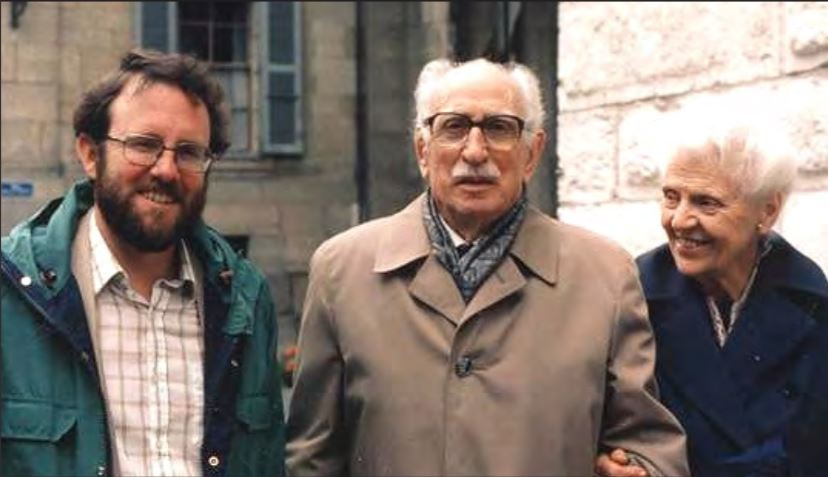

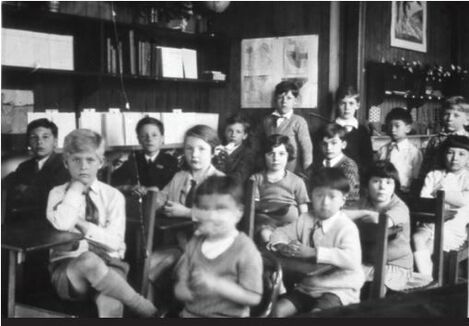

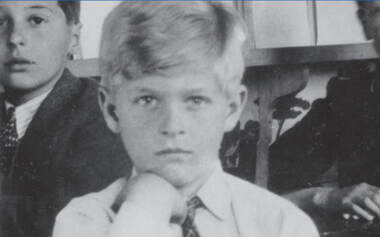

By Dan Rottenberg After the MacJannet Foundation’s annual meeting in June of 1991, Barbara and I arranged to stay on in Talloires for an additional week of sunshine and relaxation. Charlotte MacJannet, learning of our plans, asked if we could give her a ride to the opening of an art exhibit in Annecy the following Saturday. Since we had no specific plans for the week, and since this event would interrupt only one of our seven days in Talloires— and since, in any case, it was impossible to say no to Charlotte, especially in her tenth decade— I readily consented. As bad luck would have it, the weather in Talloires that week was miserable— cold and rainy from Monday through Friday. Not until Saturday— our last full day in Talloires— were we finally blessed with the hot sunny weather we had yearned for. Yet this was the day we had committed to drive Charlotte to a formal indoor event in Annecy. I was beside myself. The thought of spending my last full day on Lake Annecy in a coat and tie and trousers was more than I could bear. So I compromised by donning a knit sport shirt, shorts and sandals— all neat and fashionable, to be sure. But still…. When we picked up Charlotte in our rental car, she was elegantly dressed in suit, hat, and gloves. She slid into the front seat (Barbara had deferentially moved to the rear). As we drove toward Annecy, it was impossible for me to ignore the contrast between Charlotte’s attire and my own. “Gee,” I said dubiously, fishing for reassurance, “do you think I’m dressed appropriately?” “No, you’re not,” Charlotte replied without hesitation. “But the important thing is that you’re here, and you’re interested.” She did not mince words; neither did she insult my intelligence by contriving some diplomatic but dishonest reply. In two succinct sentences, she answered my question but also cut to the heart of the matter. In the process, she demonstrated the virtue of an uncluttered mind. I think of this incident often. For example, at a recent dinner for MacJannet Fletcher Fellows at Tufts in Medford, Mass., one of the Fellows apologized to the group for showing up in T-shirt, jeans and sneakers. Echoing Mrs. Mac, I told him: “The important thing is that you’re here, and you’re interested.” Who knew, back in 2009, what a difference the MacJannet Prize would make? By Tony Cook Just 12 years after its birth, the MacJannet Prize for Global Citizenship is an astonishing success story. Its influence has far surpassed the modest dreams of its creators (myself among them). It’s become a driving force behind the global Talloires Network of Engaged Universities, which is itself the driving force behind a revolutionary idea currently sweeping the academic world: that universities should venture beyond their cloistered towers to grapple hands-on with real-world issues. In these 12 years, more than 525 civic engagement programs on six continents have applied for the Prize, and 64 of them— in 26 countries around the world— have been honored as Prize-winners or honorable mentions. “The MacJannet Prize is our longest running program,” says Dr. Lorlene Hoyt, executive director of the Talloires Network. “It is well-known and highly regarded by higher education institutions and communities around the world.” The Prize has set the standard for what can be accomplished when students and faculty harness their skills to improve the lives of their fellow citizens. And often, the first question uttered by Prize recipients is: “Who were the MacJannets anyway? And why is there a prize named for them?” For the answer, you must journey back more than a century to Paris in 1920, when a charismatic expatriate American, Donald MacJannet, began tutoring children of American diplomats, soldiers, and business executives stationed in Europe in the wake of World War I. Within three years Donald had assembled enough charges to create a school. One of his early students was my father, Howard Cook, who attended what was then called The Elms, after the mansion the school occupied on the outskirts of Paris. When the resourceful and inspirational “Mr. Mac” subsequently launched the MacJannet Camps on the shores of Lake Annecy in 1925, young Howard followed him in 1927 for two summers. Twenty-seven years later, I myself savored a summer season at the MacJannet Camps (one for boys, one for girls) and encountered Donald and his German-born wife Charlotte. They made quite a team: Donald exuded boyish enthusiasm and a love of learning; Charlotte, for her part, conveyed artistry and discipline. Together with a staff of counselors from around the world, these two educational radicals demonstrated how activities like mountain climbing, visiting cultural landmarks, and playing games could be utilized to impart curiosity, creativity, and courage to the young people in their care. But in retrospect, the MacJannets were much more than educators. They were what we would now call “social entrepreneurs.” Ultimately, they created a farflung community of school and camp alumni who, having experienced the excitement of “learning by doing” abroad, became ambassadors of international understanding. A novel concept Eventually, the Macs and their followers created the non-profit MacJannet Foundation in 1968 to perpetuate the values that had defined their lives. (One of those followers, my father Howard Cook, served as the Foundation’s president from 1986 to 1996, and I assumed the same role from 2008 to 2013.) This incubator produced the seeds of cultural exchange programs, graduate courses in international affairs, and ultimately the MacJannets’ gift of “Le Prieuré,” the unique 11th Century priory in Talloires, France, that they restored in the 1960s and donated to Donald’s alma mater, Tufts University, in 1978. The Prieuré subsequently became the locus of an ambitious MacJannet-style study-abroad program for Tufts undergraduates as well as the gathering spot for educational conferences. At one such meeting in 2005, assembled there by Tufts’ then-president Lawrence Bacow, 29 university presidents and chancellors from 23 countries pledged their support for a then-novel concept called “civic engagement.” Traditionally, students studied in classrooms and laboratories before venturing out into the world to apply their knowledge. By contrast, the founders of what became the Talloires Network of Engaged Universities envisioned medical students pursuing public health projects, engineering students applying their development skills, and liberal arts students attacking real-world illiteracy. Without realizing it, in effect they embraced the philosophy of “learning by doing” that the MacJannets had been practicing since the 1920s. As it happened, the first executive director of the new Talloires Network was Dr. Robert Hollister, the dean of what was then called Tufts’ Tisch School of Citizenship and Public Affairs. “Rob” Hollister had also been a MacJannet camper in the 1950s– one who was named “Best All-Around Camper” two years in a row. Another camp alumnus was fellow MacJannet Foundation board member George Halsey, who had been my canoeing buddy in Talloires in 1954 when we were 12 years old. The three of us wanted to find a way to memorialize the MacJannets, who had helped shape our individual character and intellectual development. As we saw it, Donald and Charlotte epitomized the very same kind of commitment to improve the world that the Talloires Network’s universities sought to cultivate. A modest proposal For his part, Dr. Hollister imagined that a prize awarded to exemplary programs fostered by Talloires Network institutions would inspire others and benchmark those accomplishments for fellow members. As then-president of the MacJannet Foundation, I felt that a prize honoring the legacy of our founders would perpetuate their contributions to increased international understanding while simultaneously expanding our nascent virtual community of global citizens. When we proposed a partnership between the MacJannet Foundation and the Talloires Network to create the Prize, we didn’t anticipate the Network’s enthusiastic reception. Thanks to an inaugural gift from our oldest Foundation trustee, Cynthia Raymond, the MacJannet Prize program was launched in 2009. But at the time, we had no idea of the galvanizing role the MacJannet Prize would play. At first, the Prize nominees sought recognition for worthwhile but relatively small-scale university programs— building a community garden, say, or offering after-school tutoring for disadvantaged children, or collaborating with prison inmates to mount a theater production behind bars. But the scope of the submissions soon grew more ambitious. For example, Aga Khan University developed community health services to benefit squatter settlements in Karachi, Pakistan. Students at Beirut’s Université Saint-Joseph launched broad efforts to relieve the humanitarian crisis brought on by the brutal 2006 war in Lebanon. Going virtual Today, in the course of jockeying for the MacJannet Prize, many of the competing programs are tackling some of the world’s most pressing problems: breaking down social barriers, fostering sustainable development, promoting public health, addressing conflict resolution, and confronting climate change. All this for a prize whose top award has never exceeded $7,500, and whose annual cost to the MacJannet Foundation runs no more than $30,000. Even in the face of the 2020 global pandemic, the latest class of MacJannet Prize winners continued their community-building efforts. Ngee Ann Polytechnic in Singapore quickly pivoted to what its organizers called “Service Learning,” which enabled them to pursue 20 projects virtually in response to the public health crisis. These included soliciting donations of soap and other amenities for care packs distributed to migrant workers, and collecting laptops for home-based learning among low-income families. On the other side of the globe, the founders of a community entrepreneurship training program at the University of Zimbabwe in southern Africa coped with a nationwide lockdown by quickly adopting virtual coaching sessions between the program’s undergraduates and their trainees. With the support of the MacJannet Prize, its students began implementing an initiative that helps Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises by providing tailored entrepreneurship training and small revolving loans for struggling business owners. Sharing success stories The MacJannet Prize has evolved into a highly influential tool for universities to publicize their civic engagement programs. (Many Prize winners have garnered extensive coverage in local and national news media.) The winning programs, meanwhile, have provided inspiration and guidance for others. As a side benefit, the MacJannet Prize has become an important tool in recruiting universities to join the Talloires Network so they too can apply for the Prize: In just 15 years, the original nucleus of 29 Talloires Network members has grown to 417 universities and colleges in 79 countries. In 2017, the MacJanneet Foundation’s prize funds were used to enable former winners to gather at the Universidad Veracruzana in Mexico for the Talloires Network’s triennial symposium to exchange useful real-world anecdotes and best practices. In the process, says Professor Hoyt of the Talloires Network, the Prize has generated “a treasure trove of data about university civic engagement programs.” The next symposium will be a virtual gathering in September 2021, co-hosted by Tufts University and Harvard University. This year’s Prizes will be awarded at this celebration of the worldwide civic engagement movement. MacJannet Foundation trustees will participate in marking the milestone. The annual Prize process clearly has also elevated public awareness of who Donald and Charlotte were, what they stood for, and how they lived. Naming the Prize for them, it turns out, has given the award a personal face that has special meaning for the recipients. Clearly, the ripple the MacJannets generated from the shores of their summer camp in the French Alps almost a century ago has swelled into a global wave. Donald and Charlotte are buried in the Prieuré in Talloires; their ashes lie under matching stones on the ground floor, inscribed with Tufts University’s motto: “Pax et Lux” – Latin for “Peace and Light.” It’s inspiring to think that the Prize named for them has spread that same spirit far and wide. By Herbert Jacobs (Excerpted from Schoolmaster of Kings, Herbert Jacobs’s unpublished biography of Donald MacJannet.) The pupil who got the most newspaper attention was Philip—blue-eyed, flaxen-haired, “the boy with no last name.” Subjected to much kidding by his classmates because of that lack, he was sometimes called Philip of Greece. His mother, the great-granddaughter of Queen Victoria, had married into the Danish royal family, which had no surname. Philip had been raised with four older sisters, so much the center of their attention that his parents felt he needed association with boys of his own age. “Mother, do you think I can get into this?” he asked his mother wistfully when she brought him to the school and he saw a group of boys playing football. “I should think you can,” she replied. By the time she and Donald MacJannet had concluded details of Philip’s admission, the active Philip was already mingling with his future classmates. Princess Alice, Philip’s mother, told MacJannet that while the boy had plenty of originality and spontaneity, “instead of being constantly hushed up he should be working off his boundless energy by practicing games and learning Anglo-Saxon ideas of courage, fair play, and resistance. Philip should develop English characteristics, because his future will be in English-speaking lands, perhaps American, and I want him to learn English well.” Why the princess didn’t respond The princess was looking out the window, watching Philip, when MacJannet made some comment, but she did not respond. Later he learned that she had been born deaf, but had learned to read lips in English, German and Greek. Living farther up the St. Cloud slope and walking to school each morning with his governess, Philip usually arrived half an hour early. He cleaned blackboards, straightened furniture, and was always helpful and eager, though he frequently quoted his sisters’ statement that “you shouldn’t slam doors or shout loud,” MacJannet recalled. He always got chairs for visitors, would not let women serve him, carried food from the kitchen but never broke a platter. Besides loving football, he did well enough in his studies to get a silver star and even a gold one, “making great progress in his three years,” MacJannet said. He begged to be allowed to be a boarder and live at the school, but “we can’t afford it,” his mother said. The royal refugee family, in fact, had very little money. Princess Alice had opened a shop in Paris where she sold the artifacts brought with them by other Greek refugees. At the age of six, when he entered the school in 1927, Philip soon learned more about American sports and presidents than he knew about King George III and cricket. Gregarious and popular, he was a member of the school’s baseball team and lower school football captain. Accidental soaking Since MacJannet believed that physical labor, in moderation, was also good for children, he took part in the gardening, leaf raking and other duties that accompanied the academic life. MacJannet remembers him in charge of the garden hose at watering time, telling each boy firmly just when to take his turn. MacJannet got a turn too, of a different kind, when he approached to take a picture and he and the camera accidentally got a minor soaking. Prince Philip later said of those three years at the MacJannet School that “they were three of the happiest years of my life” (presumably up to the age of nine, when he left). They may, in fact, have been part of the reason why he later sent Prince Charles to school rather than having him tutored, like previous Princes of Wales. Too much laughter “Philip was keen, intelligent and responsive,” Mrs. Dorothy Huckle, a teacher at the Elms school, wrote in a letter. “Sometimes he was so boisterous that he had to be “sat on,” she continued. “One day in class something came up to make us all laugh. When I felt that we had laughed enough, I said, ‘Now, that’s enough! Let’s get on with our work.’ Philip continued to laugh, not out of bravado, but for the sheer joy of life. “‘Enough’s enough, Philip,’ I said. ‘Stop it and let’s get on with class.’ My tone of severity astonished another child, who said to me in an awe-struck voice, ‘His uncle and aunt are a king and queen!’” “There was a dead silence, and I was faced by a pack ready to defend their idol. Blue, black, gray, green and brown eyes looked at me with varied expressions— all questioning. Among them was a pair of blue eyes (Philip’s) looking straight into mine with the wisdom of ages behind them, waiting for my answer. “‘Yes, but you are Americans,’ I said. ‘You don’t believe in kings and queens. You honor a man for what he does. Any of you may be president of the United States. Philip must prove himself worthy of being the nephew of a king and queen. He must prove himself to be a prince before we take notice of that’.” “The little fellow took his reprimand like a man. He knew that he had not been sent to school to be pampered, to be singled out for favors. He was there as Philip, or Philip of Greece, if a last name was demanded— a little boy whose mother had impressed upon him the necessity of working hard, harder even than the other children.” Novice skier Philip showed the same burst of energy when he went with the MacJannet group at the 1927 Christmas holidays for two weeks of winter sports at Chamonix. Gustav Kalkun, the Estonian native who was a counselor at the MacJannet camp and ski instructor, watched Philip tumbling into the snow repeatedly, but getting up each time to try again. The next day Kalkun and his American-born wife Hally took a stiff but eager Philip between them and, with a hand and ski pole from each, the lad soon learned fast on steep slopes. Once, when Philip accidentally let go and disappeared under the snow, they had to move fast to dig him out. Besides skiing at Chamonix, Philip, in his usual role as leader, persuaded three other boys that it would be fun to appear at a costume party as chimney sweeps, and that burnt cork was the very best material for blackening faces, ears and hands. And it fell to the lot of Donald’s sister Jean MacJannet, after the party, to help in the slower and more laborious task of removing the cork from the royal face and ears. Philip was widely pictured in the French, British and American press in a Robin Hood production at the school, laughing as he drew an arrow (see photo above). Others in the picture are his classmates Jack and Anne de Bourbon, son and daughter of Prince René de Bourbon. Philip’s best friends at the school were Wellington and Freeman Koo, sons of V. K. Wellington Koo, then Chinese ambassador to France, and later a judge at the International Court at The Hague. Guests at the palace

Fifty years later, in 1977, Prince Philip invited Donald and Charlotte MacJannet to a party at Buckingham Palace as part of the Queen’s Jubilee. MacJannet, an old hand at arranging to be in the front row, found the route that Philip would take in circulating among the guests, and Philip stopped to talk. “Am I the only one of my classmates of so long ago that you keep in touch with?” Philip asked him. “Or do you just keep in touch with those who get into the newspapers?” “Try me out,” MacJannet replied. “Name someone you remember.” The prince then asked about Wellington Koo, saying, “He was kind of like me. I was known as the boy who had no last name. He had been pointed out to me as ‘Ching Ching Chinaman’.” When Philip married Princess Elizabeth in 1947, some MacJannet alumni got a shock of recognition when they saw pictures of Prince Philip at the Elms on a Boston TV station. The film, which Donald had lent to the station, showed a cracker race among some ten pupils at the school, and there was Philip, in his usual mischievous manner, his cheeks bulging with crackers, making faces at the camera. The Duke of Edinburgh was rescued from a traumatic childhood. Donald MacJannet may deserve much of the credit. From Les Entretiens, Spring 2012 BY DAN ROTTENBERG Donald and Charlotte MacJannet molded several subsequently famous figures during their formative years, among them the late Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi and the late U.S. Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart. But the MacJannets’ best-known alumnus has long mystified devoted MacJannet acolytes, not to mention many of his subjects. The Duke of Edinburgh, now the 90-year-old consort of Britain’s Queen Elizabeth II, was enrolled at Donald MacJannet’s school outside Paris in 1927, when he was a six-year-old with the less grandiloquent (if equally baffling to his classmates) name of Philip of Greece. Donald MacJannet’s approach to education, as we know, relied heavily on offering children a warm and welcoming environment as well as exposure to foreign cultures, the better to sensitize them to respect other people’s differences. Yet Philip’s public image, as London’s Telegraph put it recently, is that of a man who “has become notorious for making public gaffes” and “has gained rather a reputation for embarrassing comments and questions while on royal tours of duty.” MacJannet disciples may be tempted to wonder: In Philip’s case, did Donald MacJannet’s formula fail? Or, conversely, is there more to Philip’s story than the figure so often ridiculed in the tabloids? A recent biography of Prince Philip suggests emphatically that the answer is the latter. In Prince Philip: The Turbulent Early Life of the Man Who Married Queen Elizabeth II (Henry Holt, 2011), author Philip Eade reminds us that Philip overcame an inconceivably traumatic childhood. Smuggled out Although Philip was born in Greece to the Greek royal family, he was mostly Danish (the Greeks recruited his grandfather, a Danish prince, to be their king in the 19th Century), with German and English thrown in. When he was just a baby, a revolution ran his royal family out of Greece. Philip himself was smuggled out in a fruit crate in 1922, as his father, Prince Andrew of Greece and Denmark, evaded execution. Philip’s mother, Princess Alice of Battenberg, was born deaf; she was committed to a psychiatric clinic when Philip was eight. His father, already traumatized by his exile from his home country, shut up the family home and went off to live with his mistress, effectively leaving his young son an orphan. Thus by the time Philip was a teenager, he had lost his home, his name and identity, his family and many of his close relatives. Shuttled around to various relatives and boarding schools in Germany and Britain, Philip grew into a tough young man. Yet this smart, robust, take-charge aristocrat somehow managed to subordinate his alpha male instincts to play a lifelong supporting role to his wife— fathering her heirs, organizing her palaces, avoiding politics, and always walking a few paces behind his wife for the rest of his life. When Philip is viewed in this light—as a stable rudder for the British monarchy—the relevant question becomes: Does Donald MacJannet deserve some of the credit? Baseball before Cricket Eade’s book doesn’t address the question directly but does provide grounds for speculation. Philip spent three years at the MacJannet School—from age six to nine. Although most educators today stress the critical importance of early childhood education in shaping personality, Eade devotes just three pages to Philip’s time at the MacJannet School, which Eade describes as “a progressive American kindergarten housed in Jules Verne’s former home— a rambling old St. Cloud mansion (also since demolished) at 7 Avenue Eugenie just above the Seine, opposite the western end of the Bois de Boulogne, and shaded by the large trees that gave the school its name: The Elms.” In some respects, Philip’s exposure to foreign classmates worked just as Donald MacJannet intended. “The majority of his classmates were American,” Eade reports, “and Philip picked up something of their drawl and learned to play baseball before he played cricket. He coveted anything that came from the New York department store Macy’s and was only too pleased to swap a gold bibelot given to him by George V for a state-of-the-art three-color pencil belonging to another boy.” Chinese friends Eade quotes one of Philip’s teachers as being struck by the young prince’s precocious sense of responsibility. Having walked to school with his nanny, she recalled, he usually arrived there half an hour early, and he would fill in the time cleaning blackboards, filling inkwells, straightening the classroom furniture, picking up waste paper and watering the plants. On his first day at The Elms, Eade reports, “some of the other boys had demanded that Philip ‘fight it out’ with another new boy. After a brief scuffle, he whispered to his opponent, ‘Are you having fun?’ When the other boy admitted he wasn’t, Philip said, ‘Let’s quit,’ which they did.” “He wanted to learn to do everything,” Eade notes, “including waiting at table, his mother having taught him that ‘a gentleman does not allow a woman to wait on him.’ He also appeared to take for granted his mother’s insistence on hard work: Alice [his mother] made him do extra Greek prep three evenings a week, and asked the school to set him a daily exercise for the holidays.” When Philip first arrived at the Elms, Eade writes, “Alice had told the headmaster that her son had ‘plenty of originality and spontaneity’ and suggested that he be encouraged to work off his energy playing games and learning ‘Anglo-Saxon ideas of courage, fair play and resistance.’ She said she envisaged him ending up in an English-speaking country, perhaps America, so she wanted him to learn good English….. Alice also wanted Philip to ‘develop English characteristics’.” Biographer’s trap Eade readily acknowledges that “The accounts we have of Philip’s time at the school all emerged after his engagement to Princess Elizabeth and thus they may have been embroidered with the benefit of hindsight.” Whatever the explanation, Eade falls into the common biographer’s trap of focusing on the manner in which characteristics are transmitted from parents (in this case Philip’s mother, Alice) to children. But the blessing of an outside patron or mentor— uncluttered by familial or Freudian issues— is equally essential. The teacher Anne Sullivan— not Helen Keller’s parents— was Keller’s “miracle worker.” Was Donald MacJannet Prince Philip’s “miracle worker”? Eade doesn’t speculate. But anyone who was exposed to the MacJannets as a child must wonder how receptive another headmaster would have been to the suggestions of a mother— especially a mother like Philip’s, who was not only deaf but also, in 1927, teetering on the brink of insanity. Link to Gordonstoun

According to Schoolmaster of Kings, Herbert Jacobs’s unpublished biography of Donald MacJannet, Prince Philip later described his time at the MacJannet school as “three of the happiest years of my life.” Jacobs further suggests that Philip’s experience at the MacJannet School may have been part of the reason why he later sent his son Prince Charles to school at Gordonstoun in Scotland rather than having him tutored, as previous Princes of Wales had been. Philip himself attended Gordonstoun after it opened in 1934. Donald MacJannet was said to have been friendly with Gordonstoun’s founder, the German educational reformer Kurt Hahn, and perhaps could have influenced Philip’s decision to enroll there. In 1956 Philip created the Duke of Edinburgh’s Award, a prize for young people (age 14 to 24) whose criteria seem to have been taken directly from Donald MacJannet’s syllabus: It honors such activities as volunteer service, physical development, social and personal skills, adventurous journeys and participation in a shared activity while living away from one’s home. “Taking part builds confidence and develops self esteem,” the program’s website explains. “It requires persistence, commitment and has a lasting impact on the attitudes and outlook of all young people who do their D of E.” That comment is unsigned, but it could have been written by Philip himself, referring to his experience at The Elms. December 2020

|

© 2019 MacJannet Foundation. All rights reserved.

MacJannet Foundation

396 Washington Street, Suite 200

Wellesley Hills, MA 02481

MacJannet Foundation

396 Washington Street, Suite 200

Wellesley Hills, MA 02481