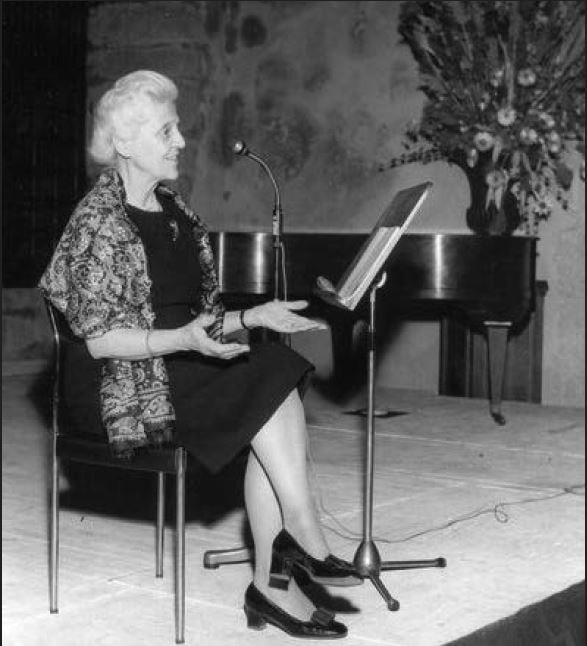

With her pipes, Priscilla Barclay teamed up with Charlotte MacJannet to find new ways to repair a shattered worldBy Selma Odom and John Habron Talloires, spring 1958: Charlotte MacJannet and Priscilla Barclay, two elegant educators in their 50s— one born German, the other English— greet colleagues at the opening of a course organized by the International Union of Dalcroze Teachers. They have gathered in the garden at the crumbling 900-year-old Prieuré, which Charlotte and her husband Donald MacJannet had recently acquired. Here Charlotte guides performers and teachers from Switzerland, Belgium, Germany, France, England, Austria, and Denmark through a ten-day exploration of “the body as an instrument for artistic expression.” Their four-person teaching team was originally trained in the methods of movement and improvised music developed by the Swiss pianist-composer Émile Jaques-Dalcroze. The curriculum includes tension and relaxation (taught by Gerda Alexander, founder of the somatic education called Eutony), body technique (with the expressionist choreographer Rosalia Chladek), group movement composition (dancer Jeanne Braun) and sensory awareness exercises for drama and opera (Gisela Jaenicke). Amid what Priscilla called the “calm beauty” of the Prieuré, Charlotte reads excerpts from Jaques-Dalcroze’s letters to his friend, the stage reformer Adolphe Appia. Chladek performs the moving solo dances Archangel Michael and Trinity. On Easter morning, Else Brems of the Royal Opera in Copenhagen sings a Bach chorale while a choir of 30 from the course expresses the same work in movement directed by Braun. The festivities include a sextet of pipers from three countries playing 17th-century airs and dances, ending with Easter eggs and daffodils for everyone. Dalcroze roots This vignette suggests how Charlotte MacJannet (1901-1999) reached out to connect people, but it also reflects the wide-ranging synergy generated by her long association with Priscilla Barclay (1905-1994) — and, by extension, the many people they touched through the connecting thread of music. After World War II, Charlotte steadily mended bridges, reunifying the Dalcroze world and helping it move toward a more inclusive future that transcended national differences. If Charlotte was the leader in this movement, Priscilla Barclay was surely her most important ally. Charlotte’s father, Otto Blensdorf, one of the first German students of Jaques-Dalcroze, founded a school for rhythm in Elberfeld in 1906. Charlotte herself went to Geneva for professional training with Jaques-Dalcroze in 1919, going on to teach in Sweden and then alongside her father and Gerda Alexander at his schools in Germany during the 1920s. She demonstrated her highly-regarded kindergarten work in the first Congrès du Rythme (Geneva 1926) and in conferences on new approaches in education. While teaching at the progressive Frensham Heights School in England from 1928 to 1930, she met Margaret James, who pioneered the making and playing of bamboo pipes. Charlotte quickly recognized their potential and integrated them in teaching solfège and improvisation. Pipes were part of the varied experience she took to France when she married Donald MacJannet in 1932. For decades, except during World War II and the postwar recovery in the 1940s, she interwove her music and leadership at the MacJannet Camps with support for the Dalcroze method and the fields (such as therapy) that it influenced. Patients respond

During Charlotte’s tenure as president of the Union Internationale des Professeurs de la Rythmique Jaques-Dalcroze (1954-1965), she visited teachers across Europe, North and South America, and the Far East to learn about the scope and diversity of Dalcroze practice. She gave talks and organized courses and conferences, always following up with detailed reports in the journal Le Rythme. She encouraged people to participate in meetings of major organizations such as the International Society for Music Education. Her goal was to motivate this community of colleagues to inspire each other, and make their teaching known. “In our kind of work,” she wrote, “sharing is the very breath of growth.” It was during the 1950s that Charlotte emerged as a champion of international understanding and openness to change, often against resistance from more cautious colleagues in the Dalcroze community. She hoped above all to build respect for differences among colleagues. This perspective shaped her huge contribution to the Jaques-Dalcroze Centenary in 1965. She not only instigated ambitious celebrations in many countries, but she also recommended speakers for the second international Congrès du Rythme in Geneva. One of her ultimate goals was to demonstrate that Eurhythmics could be successfully utilized as a therapeutic technique. Priscilla reported that Maria Scheiblauer’s film presentation, taken at a hospital, showed how the playing of a bamboo pipe aroused the first flicker of interest in profoundly disabled adults and children. Calm and authoritative After the memorable course of Easter 1958, it would be a matter of months before Priscilla Barclay returned to Talloires, this time as director of arts and crafts for the MacJannet summer camps, a role she had held for a decade. As an occupational therapist by training, Priscilla supervised children in a range of crafts: weaving, clay modeling, and making bamboo pipes. As Priscilla later described it, Charlotte was her inspiration: “From her I learned to make and play a bamboo pipe, and at one fête day, 73 children and counselors played the instruments each one had made.” Linda McJannet, a distant relative of Donald, was a camper in 1954 and remembers Priscilla as a calm and authoritative figure, who also led the children in singing French rounds. In July 1949— the camps’ first post-war summer with American campers—Priscilla wrote to her mother that she found the cultural and developmental differences between the nationalities astonishing: “The Americans are so overgrown and sophisticated,” she remarked, “and the French so much more childish and small.” Soft sound Priscilla’s contribution to the MacJannet Camps transcended music. “There is a terrific lot to do to get everything ready,” she wrote her mother in 1949, “… fixing beds and heaving around mattresses. Charlotte and I were alone the first few days. Then the American group arrived at 4 a.m. She went over to Geneva to meet the plane and I kept the soup hot.” The proximity of Talloires to the Swiss border was important for Priscilla and Charlotte, helping them remain in contact with staff and visitors at the Institut Jaques-Dalcroze in Geneva and facilitating their visits to Jaques-Dalcroze himself, a year before his death. Charlotte had a major impact on Priscilla’s professional development. Not only did she recruit her to the summer camps, she also invited Priscilla to carry out a study trip of music therapy in the U.S. during the winter of 1948-49. This was a formative experience for Priscilla: As a Dalcroze practitioner and occupational therapist, she was developing a music therapy practice at a time when America was considered advanced in this area. On the tour, which crossed seven states, she also demonstrated Dalcroze Eurhythmics in medical settings where the method was unknown. In the mid-1950s, a crucial meeting took place at Talloires between Priscilla and Dr. Doreen Firmin, physician superintendent at St. Lawrence’s Hospital, Caterham, Surrey. On returning to England in 1956, Priscilla was appointed senior occupational therapist for special work in music at St Lawrence’s. For more than 20 subsequent years, she combined Dalcroze Eurhythmics exercises, songs, drama, and bamboo pipe-making in what was the first music therapy service in the United Kingdom. Priscilla noted the way children responded to the soft sound of the pipe and how they respected instruments more if they had made their own. Toolbox preserved Despite her pioneering work in music therapy, Priscilla is remembered by the global MacJannet community primarily as a craftswoman and musician. “I still have the bamboo flute I made at Camp MacJannet 63 summers ago,” wrote former camper Bob Rottenberg in Les Entretriens in 2017. “I painted ‘1953’ on it, and found it in the cabinet in my father’s living room in New York after he died in 2013. It still plays a sweet tune!” The image on the cover of this issue—Priscilla with three budding musicians at Camp MacJannet—reflects not only the attention, discipline, and satisfaction developed through attaining a craft, but also the care for people and materials that characterized Priscilla’s work, both as a camp counsellor and a music therapist. Priscilla’s toolbox, as well as some of her pipes, now reside at the Dalcroze UK archive at the National Resource Centre for Dance, University of Surrey. The Dalcroze network that she and the MacJannets helped create lives on today as the Fédération Internationale des Enseignants de Rythmique. The International Conference of Dalcroze Studies, launched in 2013, brings together teachers, performing artists, therapists and scientists every two years, echoing Charlotte and Priscilla’s gathering at Talloires more than 60 years ago. Dr. Selma Landen Odom was founding director of the M.A. and Ph.D. programs in dance and dance studies at York University in Toronto, the first offered in Canada. Dr. John Habron is head of Music Education at the Royal Northern College of Music, UK, and Senior Research Fellow at North-West University, South Africa. He is currently undertaking a long-term research project about Priscilla Barclay and would welcome reminiscences from those who knew her. He can be reached at [email protected].

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

© 2019 MacJannet Foundation. All rights reserved.

MacJannet Foundation

396 Washington Street, Suite 200

Wellesley Hills, MA 02481

MacJannet Foundation

396 Washington Street, Suite 200

Wellesley Hills, MA 02481